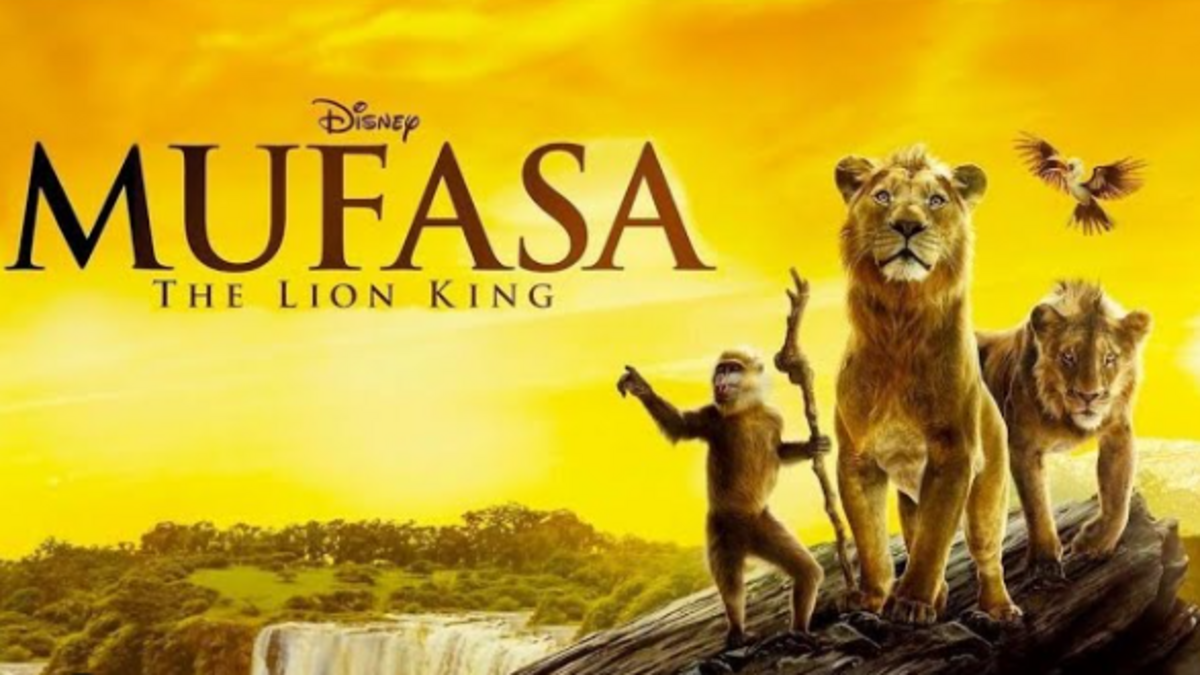

In Mufasa: The Lion King, the fur looks silkier and more luxurious, the African landscapes are bolder and brighter, but much in its horizonless kingdom remains the same. It was just five years ago that the photorealistic remake of The Lion King brought Mufasa back to life, with James Earl Jones lending his regal voice to a ruler whose benevolent dominance reflected Hollywood’s complex relationship with its supposed progressivism. By the end, villainy is vanquished, order is restored, and the hereditary monarchy is reaffirmed. The song’s message holds true: the circle of life stays reassuringly unbroken.

The circle has proven to be an ever-expanding spiral for Disney over the years. The first film, a seamless blend of old and new technology, debuted in 1994 to critical acclaim and chart-topping box office success, racking up awards and cementing the studio’s emerging status as an industry giant. In the decades that followed, the film spawned a straight-to-video follow-up, several animated TV shows, a Broadway hit, theme park attractions, and a number of Beyoncé projects. She voiced Mufasa’s queen wife, Nala, in the 2019 remake, and among these projects is Black Is King, a feature-length film version of her companion album.

Beyoncé and her daughter, Blue Ivy Carter, as a cub named Kiara, appear in Mufasa, a technologically advanced photorealistic addition to this Disney extravaganza. An origin story told largely through fragmented flashbacks, the film takes its title character on an adventure filled with dangers, none of which are human, and features the usual cast of new and returning voices. (Some are more welcome than others; Seth Rogen and Billy Eichner again voice the hyperventilated Pumbaa and Timon.) The franchise’s shepherds here are director Barry Jenkins (Moonlight), writer Jeff Nathanson, and lyricist Lin-Manuel Miranda, who contribute seven songs.

The overall results are generally handsome, mildly disturbing, occasionally monotonous, and often familiar, despite some unusually sharp, brief departures from Disney’s calming formula. Once again, the story gets off to a broad start and quickly focuses on a male cub on a journey of self-discovery, involving peril, romance, lackluster comedy, and a firm affirmation of his royal birthright that comes with a worrying side of populism. This time, Mufasa is the young hero (voiced by Braylin Rankins as a cub and by Aaron Pierre as an adult). He enters the loving embrace of his mother, Afia (Anika Noni Rose), and father, Masego (Keith David), but is soon thrust into a new territory and the circle of an adoptive family.

The makers of the original Lion King occasionally referenced Hamlet as an influence, a somewhat lofty and self-flattering comparison. This time around, however, Mufasa seems more like a lionized Charlton Heston as Moses in The Ten Commandments (1956): an outsider raised in a royal household, destined for a grand purpose, and entangled in a strained bond with his surrogate brother, Taka (voiced by Theo Somolu and Kelvin Harrison Jr.). Mufasa endures hardships and even fights against rival lions, led by Kiros (Mads Mikkelsen)—white-furred super-predators who, like previous waves of colonists in Africa, seek to dominate everything they don’t kill outright.

The introduction of a group of white robbers—and a nod to colonization—is a welcome jolt of daring in this saga. This is especially true because, like most big-studio films made for world domination, the film’s bid for verisimilitude—evident in its precise mimicry, the streaks of feathers, the bright flowers, and the billowing clouds—is in service to a movie optimized to appeal to everyone. Given the advances in digital animation (A.I. was used for the 2019 film), it’s no surprise that the fur and fangs here look more realistic than ever before. Still, the creatures still talk, sing, and amuse people in animal costumes the way they have long done in Disney films.

This is true, though the casting reveals Jenkins’ unmistakable touch. Most of the adult voices have warm, emotive expressions, with John Kani’s red-faced adult mandrill, Rafiki, making his way into every scene. The children sound similarly natural, with none of the conventional melodic voices that can become as unbearable as claws dragging on stone. Still, any hope that Jenkins is more authoritative than Disney here fades by the time the adult Mufasa sings a tepid love duet with his girlfriend, Sarabi (Tiffany Boone). Romance, as well as families and their problems, is a given in the studio’s storybook, as are the animals’ prudent dietary habits. Never fear, no one’s (literal) throats were slit in the making of this movie.

In the end, every ferociously exposed pointed tooth and outstretched claw in Mufasa remains safely blunt. That’s natural in a children’s movie, but what’s most striking about this series is that, as technology has evolved, the gulf between the natural world and ours has widened exponentially. The depiction of animal figures is now so vividly realistic that, at times, you can almost feel the velvety skin of Mufasa’s cub’s fur in your fingers, just as you would with a domestic cat. There’s something pleasant about it, even if—bad news!—it’s beginning to look as if Disney, with its galloping herds, leaping troopers, and colorful feathered flocks, is busy modeling the natural world before it disappears.